This interview was conducted in person during a retreat given by Fr. Cassian in Chicago for American oblates of the Benedictine monastery in Norcia. Fr. Cassian graciously allowed the author to publish a transcript of the interview.

Julian Kwasniewski: Did you want to become a monk at a young age?

Fr. Cassian: Well, not exactly. I wanted to become a priest at a young age. But I did not even hear about monks until I was in college.

JK: Really?

FC: I didn’t even know they existed. So that was a gift of God.

JK: Well, what was your first monastic experience, then? How did you first find out about monks?

FC: I was at Indiana University, as a freshman, which is only two hours from St. Meinrad. There were two monks from St. Meinrad at the university that year studying. And so I met them at the daily Mass crowd; that was my first contact with monks. Then, later, I went to St. Meinrad with some other friends on a kind of picnic, that’s all. There was obviously the action of God; it was like love at first sight. I was hooked immediately. I had already been thinking about changing my major and all that sort of thing and was interested in the seminary once again. Since St. Meinrad ran a seminary, I transferred from Indiana University to the college seminary at St. Meinrad in my sophomore year. I lived around monks…

JK: …and that was the end of it!

FC: Yes.

JK: So you were a monk at St. Meinrad’s first.

CF: That’s right.

JK: And when did you, from St. Meinrad, become involved with the founding of Norcia?

FC: I entered St. Meinrad in 1979. I was ordained in ’84, in April, and in June sent to Rome to study. So I had five years – I’m just giving a little sketch here – five years for my graduate studies in Rome. Afterward, I went back to St. Meinrad and taught for four years, then was sent back to Rome in ’93 to teach at the Benedictine University there. As I lived there at Sant’Anselmo, it became clear to me that I wanted a more authentic monastic life, because Sant’Anselmo takes sort of the lowest common denominator of all the monasteries in the world…and it’s not terribly satisfying. I had always been full of high monastic ideals and so was searching for what I should do. In 1995, a priest friend of mine, who was studying in Rome, he and I went on holiday together. It was while on the train from Rome to Naples that I received the inspiration to found a new monastery – from God, because it just came to me in a flash.

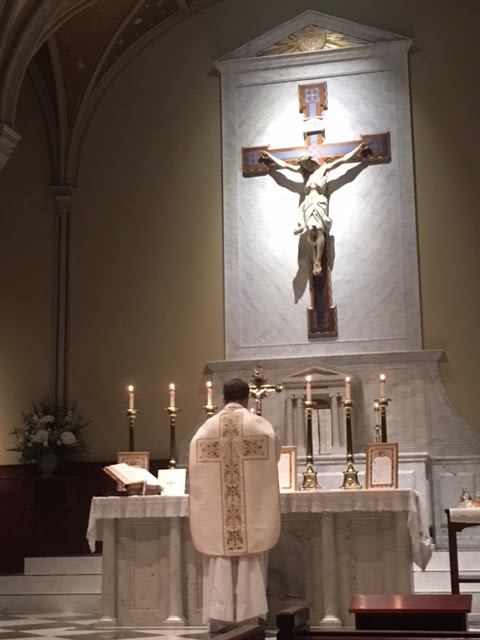

Fr. Cassian incensing the altar.

JK: Did you see something specific, like passing Norcia, or something else?

FC: No, no. I didn’t know anything about Norcia – well, I knew of its existence – but it did not enter into the picture at this point. This is 1995. I went back to St. Meinrad at Christmastime and asked the new abbot if I could make a foundation. Much to my surprise, he said, “Yes.†But it took three years for that to mature – three years of testing the spirits to see if they were from God. So it wasn’t until 1998 that the abbot primate had the project for me. He wanted to found a monastery in Rome, at Sant’Anselmo (where I still was), to care for the place and supply manpower for the Benedictine university there. So between my inspiration and the abbot primate’s desire, that’s how the monastery was founded, in Rome, in 1998. It moved to Norcia two years later because the abbot primate had a heart attack and resigned in September of 2000, and I needed to find a new solution for the life of the community because he had basically been our “protector.†At that time, the bishop of Spoleto-Norcia invited us to transfer to Norcia, to re-establish monastic life at the very birthplace of St. Benedict. So that’s how we got to Norcia, in late November of 2000.

JK: Now you were ordained in, and all your experience at St. Meinrad was in, the Novus Ordo?

FC: Correct.

JK: How, then, did you find out about the traditional Mass?

FC: Well…in a gradual way. That is, at Sant’Anselmo, as a student, I belonged to the “Latin Chapel,†as there were different language groups that prayed Lauds and Mass together every day. I gravitated toward the Latin Chapel, learning how to offer the New Mass, in Latin. I studied Latin with a famous Latinist in Rome while I was doing my other studies there, so I discovered the beauty of the Roman Rite in Latin – but the Novus Ordo – and with the chant. I also learned the chant repertoire, which is mostly the same as that of the Usus Antiquior.

And here’s another step to the Old Mass: I was very interested, because of my studies in liturgy, in the Byzantine Rite. One summer, I spent two months in Greece living in a Byzantine House of Studies, going to the Holy Mountain (Mount Athos). I was asked even to live at the Greek college in Rome, to assist there. It didn’t work out, but I was interested. Through the Byzantine Rite I discovered a different ethos of liturgy. Now, that’s important; I discovered the traditional Latin Mass through the Byzantine Rite, because of the very similar ethos.

It was not until ’93 or ’94, when I returned to Sant’Anselmo to teach, that I met a monk from Le Barroux who was also studying there. He invited me to go and visit them, and I did. It was an experience similar to the one I had at St. Meinrad in 1973 – of being just blown off my feet! When I experienced the Liturgy there, I thought, “Oh! Well, this is what it’s supposed to be like!†It was this kind of insight. A moment of insight. Extraordinarily beautiful. It just took my breath away, because of that beauty. I had already studied the orations from an academic point of view (liturgical history and all those things), so it was sort of the way of the whole thing coming together in a unit.

JK: While we are talking about beauty in the Mass, and specifically in the Old Mass, could you comment a little bit on the way that, in your experience, the celebration of Mass can be related to the verse in Scripture that says, “Enoch walked with the Lord and was seen no more, for God took him�

FC: That’s interesting…what connection do you see there?

JK: Well, the priest as an alter Christus… How is it that in the Mass, God takes the priest, and he is seen no more? And how is this the case in the Old Mass, but not in the New?

FC: Ah, very good. That’s wonderful – that is, it is an important insight, and it is wonderful that you connect that passage with it.

JK: It’s just an odd expression…curious, one might say.

FC: You’re absolutely right. In the Old Mass, the personality of the priest does not matter. His office matters, and he and the people together are facing the Lord. Conversus ad Dominum. And for that reason the role of the priest is an objective one. It’s not subjective, and for that reason he disappears. That is, obviously, he is the mediator between the congregation and God, leading the congregation toward God, but because of the objectivity of the structure, he disappears. That is very salutary, because the Mass is not about the priest; it’s about God. In the Novus Ordo, because of the versus populum practice, and because of all the options of the priest inserting something like a comment, or spontaneity, the role of the priest becomes terribly subjective. Therefore, he becomes the focus of attention, so the New Mass is terribly clericalized because it’s all about the priest, as opposed to the Old Mass. And this is unfortunate.

JK: People sometimes say, “Oh, there’s too much respect paid to the priest in the Old Mass,†like all the kissings of his hands and moving things for him and things of that sort, but really the Novus Ordo, in fact, makes a much greater deal of the priest.

FC: That’s right.

JK: In Compline we have the verse: “Offer up the sacrifice of praise and trust in the Lord; for many say, Who sheweth us good things?†Can you talk about how young men today are not being shown “good things†liturgically, and how they won’t be attracted to God, to a priestly or monastic vocation, unless they see this beauty in the liturgy?

FC: The good things are abundant. The Tradition of our faith, our liturgy, our prayer, our mysticism…those good things are extraordinary and available but not presented to people, not known…forgotten, in large part. So young men don’t see those good things. They see other manifestations of the Church, which, in the practice after the Council, tend to be very horizontal and earthly oriented: “social action†and “doing good.†Well, doing good, of course, is important and good, but the transcendent is often missing. Simply “doing good†is not enough of a motivation for giving your entire life to God. That motivation has to be union with God. I think we have really cheated ourselves by abandoning that wealth of tradition, which focuses on God. It doesn’t neglect good works, for heaven’s sake! But it focuses on God.

JK: Talking about monastic life, and as one who has seen a lot of vocations – some that worked and others that didn’t – how would you reflect on the words of Christ: “Many are called, but few are chosen� It seems mysterious; many are called but few chosen?

FC: I would interpret it this way: it is not that God calls many and then sort of sifts through them and chooses only some of those. I think it is rather, “Many are called, but few respond†– that sense of being chosen. And few respond because, like the rich young man in the Gospel, there are many things that in a superficial way seem more attractive. And if they could only experience the transcendence that we spoke of earlier, they would see another beauty. Then things would change for them.

JK: In conversation with people who attend the traditional liturgy, one hears so frequently: “Oh, I was captured by the beauty of the Mass.†But going back a little, do you remember anything of your first Mass?

FC: No, nothing. But here’s something curious: in the monastic way of looking at things, the monastic vocation is primary, and the priesthood is secondary. Now, that runs contrary to the way a lot of pious people think. That would be somewhat scandalous, perhaps. But that’s the way it is in the monastery: your monastic commitment is primary, and the priesthood is secondary. The priesthood is splendid, wonderful, but it means that the life of the monk-priest (if I can put a hyphen there) does whatever kind of work needs to be done in the monastery. He might be assigned to say Mass; he might be assigned to wash the dishes. He might be assigned to hear confessions, or he might be assigned to sweep the floor. In a certain sense, all of that is harmonious; in one sense, it does not matter. The care of souls on the part of the monk-priest is something that is integrated into his monastic life. It’s not the “be-all and end-all†of his vocation; it’s an outgrowth of the monastic charism. So there is a whole different view of the priesthood from [that of] the diocesan priesthood where it is the “be-all and end-all,†whereas for the monk, being a monk is the “be-all and end-all.â€

JK: That makes sense. So, talking of this monastic vocation, according to my parents, when I was about five years old, I asked you what it was like to be a monk, and you said, “It’s wonderful!†Could you say a little bit more about this? What is the attractiveness of the monastic vocation? How it is wonderful?

FC: What’s wonderful about the monastic vocation is God, in the first place. Perhaps I could tell a little anecdote. Maybe that will describe it better. When I was a small boy, about five years old, my mother gave me a children’s Bible storybook. I was a precocious child, as you were, and could read at five years old and was happy to read this Bible storybook. So I came across this story about Exodus 3 and the burning bush. I remember reading it, because it was not dumbed down, and it was recorded, as Scripture says, what God says from the Bush: He said His Name, “I AM WHO AM.†Even as a child of five years old, I thought, “Well, nobody talks like that. That’s very strange!†I felt the wonderful attractiveness of God in that strangeness, in His revealing His Name…a very odd name. In the monastic life, there are all kinds of moments like that when you encounter the living God. That being the goal – and, as St. John Cassian describes, the indwelling of the Holy Spirit and the daily visitation of Christ in the soul – the rest of the life is ordered to that, which means asceticism and struggling with your vices and recognition of reality the way it is, and trying to order all things to the worship of God, which means beauty and music and liturgy and architecture, everything. But it is also focused on that hunger for God, that desire for God. For me, there is nothing else in the world I would rather do.

JK: So the monastic life – the heart of it – is the daily visitation of God. And there’s nothing that gets better than that in life!

FC: Yes. It’s a great summary.